"What can be explained is not poetry." -W.B. Yeats

This post is about autism and how it may affect the ability to narrate. Points made may not apply to other individuals on the spectrum and are NOT meant to imply that narration is a problem for all autistics.

Narration or the Lack of it

In its most basic sense narration is the act of telling a story. But narration is more than storytelling. As autism researcher Matthew Belmonte points out, we move from chaos to meaning through narration:

A fear of death drives us to become narrators, to transform the disconnected chaos of our sensorium into representative mental texts whose distinct scenes contain recognisable characters that act in coherent plots. (Matthew Belmonte, More Than Human)

From this perspective, narration is what we do to make sense of our lives.

Familiar narrative structures include the three acts structure (beginning, middle and end), primary literary categories (poem, novel, play), and specific fiction and nonfiction genres. Meaning is found in the overarching message these narratives convey.

Even everyday stories are usually told in three acts and, while some people are better at storytelling than others, most can construct a narrative without giving it a whole lot of thought. The neurobiology of narration, however, isn't as straightforward as we might expect.

According to Belmonte, our ability to narrate depends on the "coordination of activity amongst widely separated brain regions." In autism, Belmonte writes, brain regions that are "more or less intact" may not be "coordinated or modulated in response to cognitive demands."

This is essentially a networking issue where "a disrupted neural organisation implies disrupted narrative organisation." (Belmonte)

This is not to say that the narratives of neurotypical people are necessarily better or more authentic than that of autistics. Only that, in terms of prevailing expectations, neurotypicals find the stories themselves easier to organize and construct.

Writers on the Spectrum

It is simple, to ache in the bone, or the rind — But gimlets — among the nerve — Mangle daintier — terribler — Like a panther in the glove (Emily Dickinson)

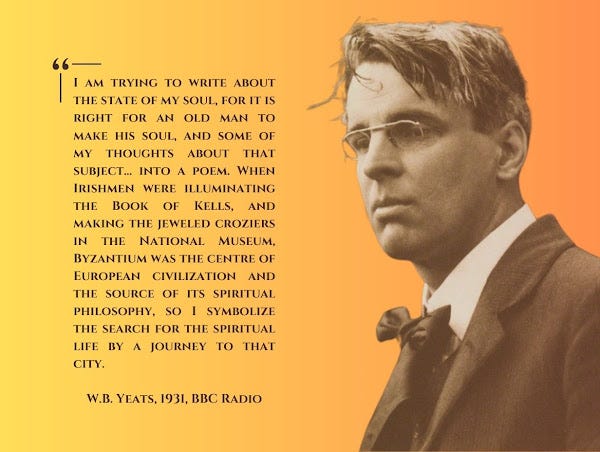

In Writers on the Spectrum, Clatsop Community College professor and literary critic Julie Brown focuses on eight important writers thought to be autistic. They are Hans Christian Andersen, Henry David Thoreau, Herman Melville, Emily Dickinson, Lewis Carroll, William Butler Yeats, Sherwood Anderson, and Opal Whiteley.

All of these writers struggled socially. Emily Dickinson once pressed a flower into an editor's hand and awkwardly told him that "this may serve as my introduction." Yeats was asked to leave the Theosophical Society because he asked too many questions. Thoreau withdrew to his cabin by the pond and was happier alone than he had ever been in company.

Their issues with writing, and in life, did not begin or end, with these examples—and Brown provides additional material to support her claim (and that of several respected psychologists) that these authors were (most likely) autistic.

The heart of Brown's book, however, is the idea that autistic writers may have trouble with specific aspects of writing. The list of issues that Brown, and others, have identified follows (with possible causes in parentheses).

It bears repeating that these issues are NOT problems for all autistics and that few autistics will demonstrate all of them.

A messy writing process (possibly due to autistic issues with abstract, linear processes)

Difficulty writing for an audience (autistic theory of mind issues)

Problems adhering to a genre expectations (oppositional or nonconformist tendencies in some autistics)

Struggles in building a narrative structure (autistic tendency to view life, and writing, as "an incoherent series of unconnected events" - Bernard Rimland )

Issues with character arc and character development (impaired relationships and understanding of human nature in some autistics)

Strong use of setting that may overwhelm the reader (exceptional memory and eye for detail in some autistic people and possible tendency of some to form an unusually strong connection with place).

Rich use of symbolism which may not be comprehensible to all readers (possible autistic tendency towards associative thinking - Kristin Chew)

Brown then analyzes the work of the writers featured for these specific issues—and finds them.

According to Brown, all eight writers showed "a marked resistance against the writing of novels" because of the difficulty they experienced in creating a "sustained, organically whole fictional narrative."

For me, this was an important insight.

I did identify with most of the other issues listed above—as well as some of the less common traits mentioned, like basing characters on oneself (which can make aggressive critique groups difficult) and the tendency to create duplicate or parallel characters. Still, for me, issues with narrative structure has been, and continues to be, my biggest stumbling block.

Ś is not autistic herself but has an autistic child and works with autistic writers in her role as an educator—says it is common for writers on the spectrum to struggle with plot / structure.

Overcoming Challenges

Irish poets learn your trade. Sing whatever is well made... (W.B. Yeats, Under Ben Bulben)

Writing a well plotted novel has always been challenging for me. And when I say challenging, I mean that I have tried to do it dozens, if not hundreds of times—without success. I abandoned most of those unsuccessful manuscripts without finishing them. Those I completed had serious structural defects.

The point of this blog post isn't that autistics can't write novels because some obviously can. The point is that long-form fiction is a difficult proposition for many—including me. This is something I have experienced over and over again. But I couldn't address the challenge until I understood why it was happening.

Writing a novel has been a dream of mine for a very long time and it's hard to just walk away from it. But change can serve a purpose, and I think the writers featured in Writers on the Spectrum prove that point.

Hans Christian Anderson switched from long-form fiction to fairy tales still read today. Thoreau gave up on society and inspired a nation. Yeats left the Theosophical Society and embraced the mythology of Ireland. Sherwood Anderson stopped writing books and created a brand new genre.

Dead Dreams and Do Overs

The genre Sherwood Anderson launched with the publication of his book Winesburg, Ohio is called the 'short story cycle.' I would like to try my own short story cycle at some point. But I'm going to publish the vampire story, which is and will be atypical for its genre, first.

I may never write a successful novel. But it's exciting to imagine myself writing (and finishing) short stories and novellas or the occasional unconventional novel—and I like the idea of challenging the status quo.

My track record for finishing things isn't the best, but I have always been able to pull a new creative project out of the ashes. In the wake of my ASD diagnosis, I understand this ability to be one among the constellation of traits we call autism.

According to psychologist Michael Fitzgerald autistics have "the ability to focus intensely on a topic...for very long periods..." as well as "a remarkable capacity for persistence...an enormous capacity for curiosity and a compulsion to understand and make sense of the world."

Fitzgerald goes on to say, "they do not give up when obstacles to their creativity are encountered," and this is not a bad thing.

'It was a curious dream, dear, certainly: but now run in to your tea; it’s getting late.' So Alice got up and ran off... But her sister sat still just as she left her, leaning her head on her hand, watching the setting sun, and thinking of little Alice and all her wonderful Adventures, till she too began dreaming after a fashion, and... the whole place around her became alive with the strange creatures of her little sister’s dream. (Lewis Carroll, Alice's Adventures in Wonderland)

Resources:

Writers on the Spectrum by Julie Brown (literary professor and critic)

Human But More So by Matthew Belmonte (research psychologist)

Autism and Creativity by Michael Fitzgerald (research psychologist)

Nobody Nowhere by Donna Williams, specifically the intro by Bernard Rimland (research psychologist)

For more on autism and writing please see:

Writing On The Spectrum

I was diagnosed with autism in 2022 and started to blog on it in 2023. I was going to write about the intersection of autism and writing. Instead, I spent the next few months sharing poetry and odd bits of prose.